When I was 16 I thought about dropping out of high school. Not because I was delinquent or because I wanted to have more time to smoke weed or anything like that. I thought, with conviction, that I would be able to learn everything I ever needed to know from the internet. It didn’t matter that I didn’t have anything I particularly wanted to do with my life, other than maybe make music and maybe write fantasy novels; I had figured out that all I needed was Wikipedia and YouTube and whatever free courses were on Udemy or Coursera and so on.

This was 2013 or so, when online courses were starting to market themselves as basically being alternatives to going to college, or college courses that were more accessible and available to everyone. It seemed a world was opening up to me, and I spent a lot of evenings scrolling through course curriculums and imagining an alternate life for myself, in which I would be entirely self-directed, self-motivated, and somehow not have to worry about supporting myself. And in that fantasy I could know everything, do everything, be the best at everything. It was a very seductive fantasy for a teenage boy to have.

And now, long story short, after not having dropped out, having gone to college and basically just doing everything normal, well adjusted, middle class Americans do, I look back and I wonder if that was possibly a dangerous mindset that I picked up in those years.

Not to say that I have remained so self-assured—definitely the contrary. I think I’ve been fortunate to have this idea (that everything can be learned on the internet) challenged enough to where my viewpoint on the matter has completely flipped.

So let me tell you about it.

I should note that most of the examples I’ll give here are related to learning music, but as we are living in a time of mass dis-information, I think this piece could be relevant to learning just about anything else, be it some skill you’ve always wanted to acquire or just reading the latest on the coronavirus (and here I date this article irreversibly).

I’d like to say that you can learn anything on the internet, but I’m not sure it’s true. The jury is still out, as far as I’m concerned. But a lot of people keep repeating the idea that you can learn whatever you want by watching Youtube videos. And, as I’ll get to later, you really kind of can. But at the same time this advice seems to be completely at odds with the conventional wisdom that you shouldn’t believe everything you read on the internet. So amidst all the noise that we experience on our various apps every day, who’s right? Where can you go for information?

I think if you’re after knowledge or information on the internet, the question shouldn’t be “where” the good sources are, and in fact there probably shouldn’t be a question at all. As we’ve all just learned, even when there’s broad agreement about a reputable source (like the CDC) you can’t just go blindly trusting everything they say (I’m referring to the 5 day quarantine thing, which at the time of writing was just announced a week or two ago).

I mean, this is pretty simple stuff. I think most of us young people learned long ago that you shouldn’t believe what you read on the internet. But we go on reading, and believing, in part I think because this other idea has crept in, which is what 16-year-old me was sold on: all information is available on the internet now, and you just have to find it.

So even when we read something we don’t believe, we spend hours trying to discredit it, or fact-check it with other sources, or find out who wrote the article and see what their deal is, or just argue back and forth in comments and threads trying to prove our superiority. Isn’t there some echo of that same 16-year-old male ego in there, in all that self-righteousness? In trying to find truth, we are driving ourselves insane.

Even just the time it takes out of your day to do any of the above is insane. You could be doing something you actually want to do. Like learn how to play an instrument. How to go about doing that? Oh right, the internet.

So on the subject of education again, how does it actually work when you try to learn stuff on the internet? Well, it’s complicated. Sometimes it works really well. Like if you need to open a can without a can opener, you can probably find out how to do that really fast. Or if you want to learn the basics of knitting, or how to play some chords on the guitar.

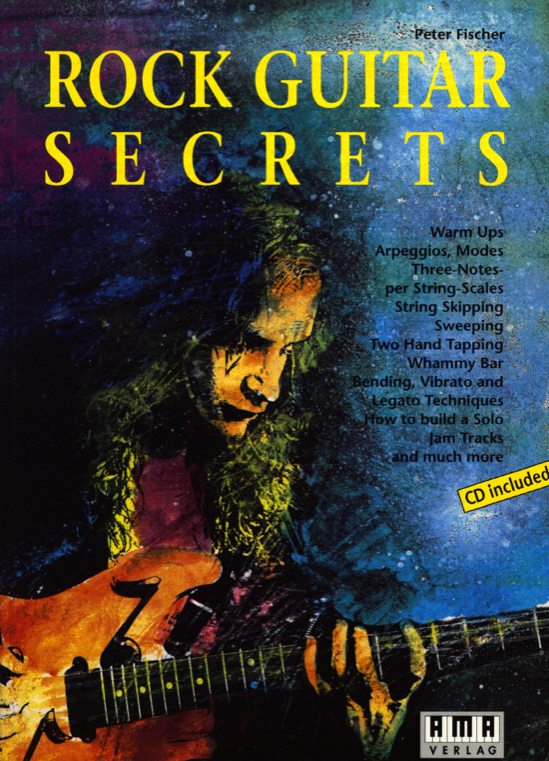

You can actually progress pretty well in a lot of skills because Youtube sort of takes the place of the kind of monkey-see, monkey-do learning we do in classes or with personal instructors. You get to watch someone do the thing, and then you can absorb not only the basic steps of whatever you’re trying to do, but often many of the subtleties involved. Like with learning guitar, you learn not only where to put your fingers but you get a sense of how hard to press down, and how to position your hand. That is, if you’re paying attention.

When you move on to the deeper levels of learning a skill, the finer details, it’s a bit less straightforward. There are a million basic tutorials for just about anything. And then there’s starting to be a lot of intermediate content too. Like, once you know some chords and some music theory and how to play the instrument, you can start to learn just from Youtube videos how to write a certain kind of chord progression, and what musical ingredients make certain styles of music sound a certain way, and how you can harness those ingredients to better write music in that style. This is fairly advanced stuff, and it’s amazing that it’s so accessible and available.

So what’s the catch? Well the problem with all of this became apparent to me when trying to learn how to specifically record and produce music. I went looking for knowledge, in my case it was stuff like, how do you get the low end of a song to sound good, and was met with tutorial after tutorial made by (not to unnecessarily throw shade) a whole lot of amateurs. Mostly if not all young men, with various contradicting ideas on how to make your song sound better. All with credentials that did not include any music I would ever want to listen to. I mean, up to a certain point, you don’t need to learn from someone who has mastered their craft; like, I could probably teach you how to play some chords on guitar, but I might not be able to teach you the finer points of playing a guitar concerto. There’s a measurable difference between musicians who can play all the notes in a piece and musicians who can play a piece in such a way that it actually moves you, and it is my belief that if you’re looking for how to get from the former point to the latter you need some instruction from someone who has at least dabbled in achieving the latter.

Going back to mixing the low end, it’s probably more worthwhile to spend your time learning from someone who has actually mixed some songs that sound good and maybe actually move you emotionally, whether you have them there in person or you’re learning from a book they’ve written, or watching a video they made on the internet, or whatever. This is why courses like Mix with the Masters exist. And other “masterclasses” that I keep seeing ads for. These are probably good courses, you can probably learn something from them; I’m not judging them one way or another. I’m just saying they exist to fill this need of learning from someone with experience in the field, but on the internet.

The point I’m getting to is not that you have to seek out the wise masters of whatever you’re trying to learn.

If you’re setting out to learn something on the internet and you’re somewhat serious about like, being good at whatever it is you want to learn, you have to suss out your sources.

You have to do all the things you probably learned in school when you had the school librarian come in and give you a primer in research etiquette and how to fact check, and what a reputable source is, and what plagiarism is, and so on. You have to check who is writing the articles you’re reading, and make sure they’re someone you actually want to be reading. Research the person behind the Youtube personality and find out what kind of life they’ve had. If they really do have a lot of experience in some field, then great, what they have to say is probably good advice. But at the same time you have to remember that Youtube videos make their profit based on views, which influences what kinds of videos get made, which may mean that your interests in learning something are not aligned with the video-maker’s interest in making money from your eyeballs.

But take this all with a grain of salt. Obviously there is valuable info on the net. I’ve learned basically everything I know from the internet.

The idea here is that there is a price to this seemingly “free” knowledge, and the price is the time you spend sussing out your sources (or the consequences of learning from someone who doesn’t really know what they’re talking about, which also amounts to lost time).

At some point this price may well be higher than the price of, say, checking out a book on the subject from the library, or buying one from a bookstore (ideally not Amazon), or taking a class in real life, or asking around until you find someone who is knowledgeable in the area you want to learn about.

So that is just something to consider. You can weigh those prices against each other. Don’t believe everything you read on the internet, and don’t assume that the information you’re getting is free just because it’s on the internet.

As an addendum, I think I should point out why books are often better sources than internet articles (this may be obvious): if a book—specifically one that is like a manual or a handbook or an instructional book, or a reference material—has been published, there’s been a fair amount of thought put into making it a useful product. Time has been invested in ensuring that the book was good enough that you, the consumer, would find it useful enough to buy and, because word of mouth used to be the best way to spread the word about a good book, you would tell anyone else who was looking for that particular information about how you found just the thing, and it was a great book to have around. Publishing a book takes significant time and resources. Writing a brief article or making a video for Youtube… might take some time and resources, but in a lot of cases the scale of production just isn’t comparable to printing thousands of copies. Of course books aren’t infallible and you must think for yourself and be skeptical and check your sources just like you learned in school, but the chances are flat out better from the outset that the information in a book that a publisher has put out will actually be more useful than what you find on the internet, simply because a) it’s usually a bit of a scandal when a book is proven to be poorly researched, and that’s bad for the publisher, and b) no one wants to get sued and c) a publisher probably isn’t going to be interested in publishing an instructional book or reference material written by an amateur in their field.